Why this matters

“Data quality” becomes political when it is undefined. One person means accuracy, another means freshness, a third means duplicates. If you do not separate these dimensions, you cannot measure improvement and you cannot agree on what “good” means.

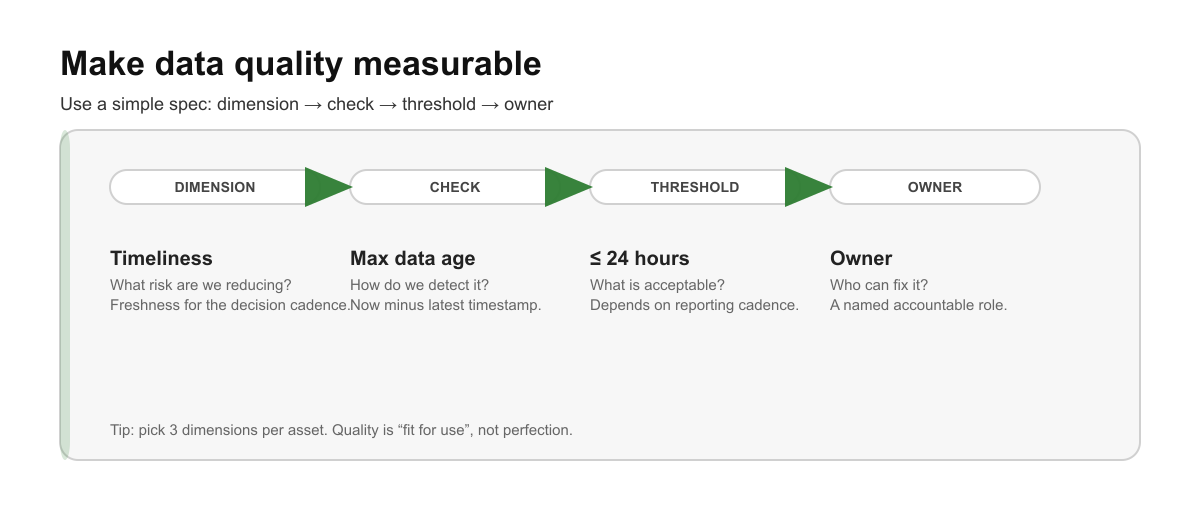

A simple governance-friendly pattern is: dimension → check → threshold → owner. Purview helps once you know what you want to measure, but the definitions come first.

The concept: dimension → check → threshold

Think of a data quality dimension as the type of risk you are trying to reduce. Then you make it measurable with a check, and you make it actionable with a threshold.

Here is a concrete example you can reuse: Timeliness means “is this data fresh enough for the decision cadence?”. One simple check is the max data age in hours, computed as “now minus the latest timestamp in the dataset”. Then you set a threshold that matches reality, for example “<= 24 hours for a daily operational report”.

The key idea is that thresholds are not universal. They are “fit for use”.

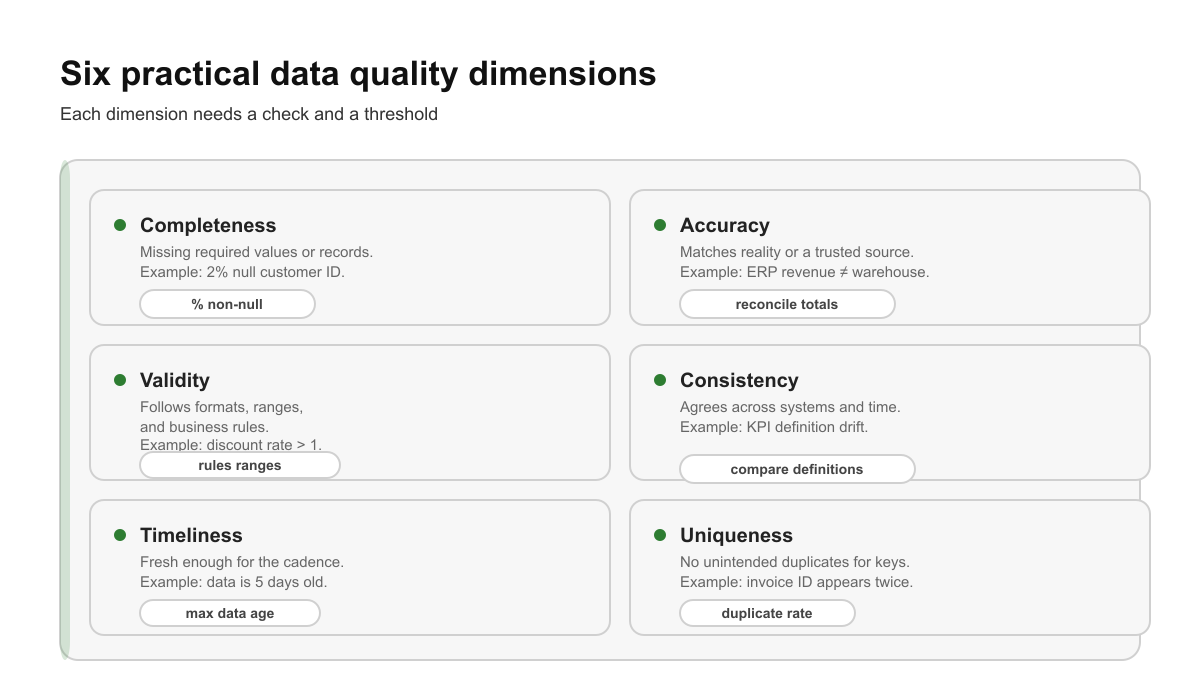

The core data quality dimensions (practical definitions)

You will see many lists in the wild. To keep this operational, I recommend starting with six dimensions that cover most real-world issues.

The goal is not to memorize a framework. The goal is to be able to translate a vague complaint like “the data is bad” into one specific dimension, and then into one measurable check.

Here are short, practical definitions you can use in stakeholder conversations:

Completeness is about missing values or missing records. If your process expects a customer ID for every order, nulls are a completeness problem. If entire days of orders are missing, that is also completeness.

Accuracy is about truth. It is easiest when you have a system of record or a trusted reference to reconcile against. Without a reference, you often have to use proxy signals and be explicit about limitations.

Validity is about rule conformance. Think allowed value lists, patterns, ranges, and business constraints. Validity checks are usually cheap and should be part of your data pipeline.

Consistency is about agreement. The same term should mean the same thing across systems and time. Consistency is where KPI definition drift lives.

Timeliness is about freshness relative to usage. A dataset that is 48 hours old might be perfectly fine for a weekly steering dashboard, and completely unusable for daily operations.

Uniqueness is about duplicates where you expect uniqueness. Duplicates inflate counts and sums, and they silently break trust because the numbers look plausible

Worked example: one governed asset, three dimensions

Pick one asset that you cataloged or scanned. For example: SalesOrders used for a weekly performance report.

For a weekly cadence, you might define quality like this:

Timeliness: Check the max data age in hours, and set a threshold such as “<= 48 hours”.

Completeness: Check percent non-null for required fields like customer_id and order_date, with a threshold such as “>= 99.5%”.

Validity: Check hard constraints like order_amount >= 0 and that currency_code is in an allowed list. For hard constraints, “100% valid” is often a reasonable standard because invalid records are not usable.

Once these are defined, you can implement the checks in your data platform. In Purview, this also becomes easier to communicate because your quality signals have clear meaning.

Checklist

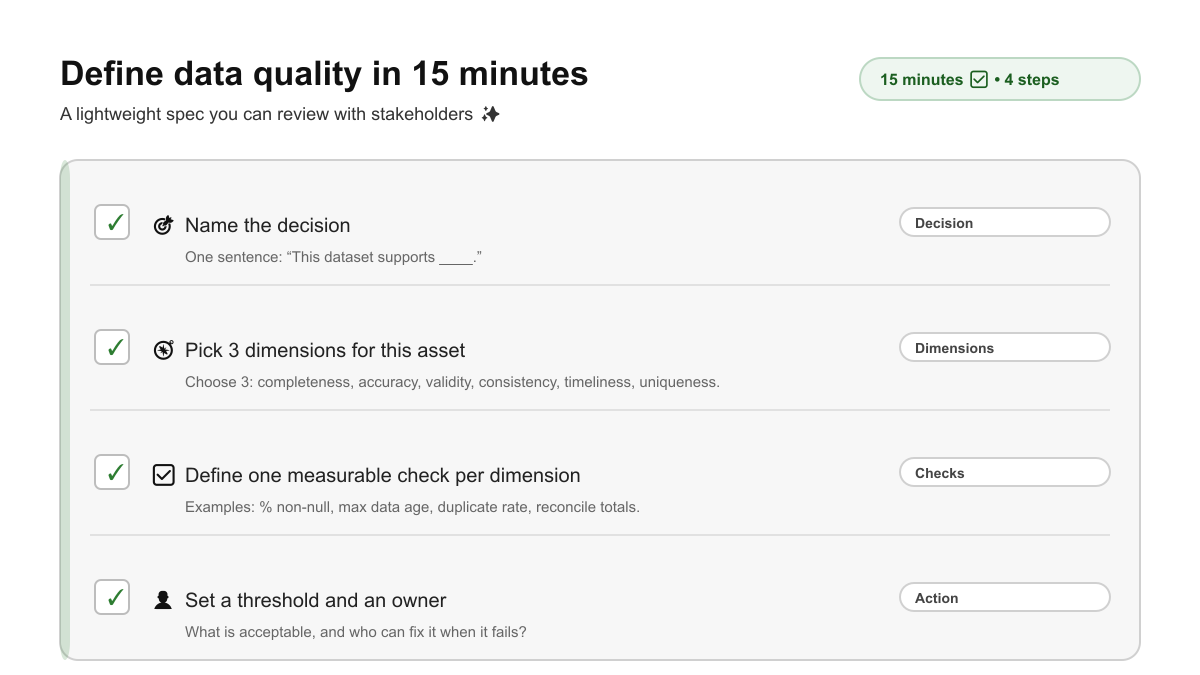

If you only take one thing from this, make it this: define quality so it can be measured and acted on.

Do: pick 3 dimensions per data product, write a plain-English definition, define one check and one threshold, and assign an owner who can actually fix issues.

Avoid: one generic “quality score” with no explanation, thresholds without context (“99.9% because it sounds good”), and hiding known limitations. Document what the checks do and do not cover.

Practice

Task: Define quality for one asset in 15 minutes.

- Write the decision the asset supports.

- Pick 3 dimensions.

- For each, write: definition, one check, one threshold, one owner.

FAQ / edge cases (optional)

Do I need all dimensions for every dataset? No. Pick the smallest set that protects the decision.

What about lineage and governance? Lineage helps you assess impact when a quality check fails, but the quality definition still starts with dimensions.

If you found this useful:

- Follow on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/florian-detzel/

- Follow on TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@bi.academy1337

- Subscribe to the BI Academy newsletter: https://bi-academy.org/newsletter